View Other Topics.

Jul 19, 2018

Jul 19, 2018

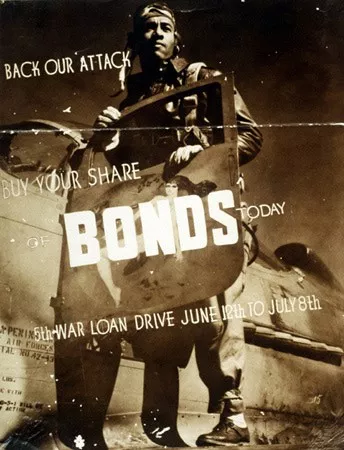

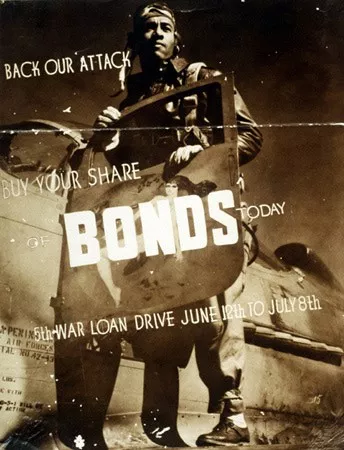

Image: US Army Air Force Training war bond poster featuring a Tuskegee Airman pilot - Tiskegee Airman National Historic Site

In this article from www.nps.gov we learn of the founding and distinctive service of America's unsung black servicemen.

Training for War

Tuskegee, Alabama, became the focal point for the training of African-American military pilots during World War II. Tuskegee Institute received a contract from the military and provided primary flight training while the army built a separate, segregated base, Tuskegee Army Air Field (also referred to as the Advanced Flying School) for advanced training. Support personnel were trained at Chanute Field in Illinois.

The first class, which included student officer Capt. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., began training on July 19, 1941. Rigorous training in subjects such as meteorology, navigation, and instruments was provided in ground school. Successful cadets then transferred to the segregated Tuskegee Army Air Field to complete Army Air Corps pilot training. The Air Corps oversaw training at Tuskegee Institute, providing aircraft, textbooks, flying clothes, parachutes, and mechanic suits while Tuskegee Institute provided full facilities for the aircraft and personnel. Lt. Col. Noel F. Parrish, base commander from 1942-46, worked to lessen the impact of segregation on the cadets.

Image of Eleanor Roosevelt with Charles "Chief" Anderson Many cadets got their primary flight instruction at Moton Field, Tuskegee, from Charles A. "Chief" Anderson. The first class of five African-American aviation cadets earned their silver wings to become the nation's first black military pilots in March 1942. Between 1941 and 1945, Tuskegee trained over 1,000 black aviators for the war effort.

Airmen in Combat

The 99th Fighter Squadron was sent to North Africa in April 1943 for combat duty. They were joined by the 100th, 301st, and 302nd African-American fighter squadrons. Together these squadrons formed the 332nd fighter group. The transition from training to actual combat wasn't always smooth given the racial tensions of the time. However, the Airmen overcame the obstacles posed by segregation. Under the able command of Col. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., the well-trained and highly motivated 332nd flew successful missions over Sicily, the Mediterranean, and North Africa.

Bomber crews named the Tuskegee Airmen "Red-Tail Angels" after the red tail markings on their aircraft. Also known as "Black" or "Lonely Eagles," the German Luftwaffe called them "Black Bird Men." The Tuskegee Airmen flew in the Mediterranean theater of operations. The Airmen completed 15,000 sorties in approximately 1,500 missions, destroyed over 260 enemy aircraft, sank one enemy destroyer, and demolished numerous enemy installations. Several aviators died in combat. The Tuskegee Airmen were awarded numerous high honors, including Distinguished Flying Crosses, Legions of Merit, Silver Stars, Purple Hearts, the Croix de Guerre, and the Red Star of Yugoslavia. A Distinguished Unit Citation was awarded to the 332nd Fighter Group for "outstanding performance and extraordinary heroism" in 1945.

The Tuskegee Airmen of the 477th Bombardment Group never saw action in WWII. However, they staged a peaceful, non-violent protest for equal rights at Freeman Field, Indiana, in April 1945.

Their achievements proved conclusively that the Tuskegee Airmen were highly disciplined and capable fighters. They earned the respect of fellow bomber crews and of military leaders. Having fought America's enemies abroad, the Tuskegee Airmen returned to America to join the struggle to win equality at home.

Moton Field

Moton Field was the only primary flight facility for African-American pilot candidates in the U.S. Army Air Corps (Army Air Forces) during World War II. It was named for Robert Russa Moton, second president of Tuskegee Institute. Moton Field was built between 1940-1942 with funding from the Julius Rosenwald Fund to provide primary flight training under a contract with the U.S. military. Staff from Maxwell Field, Montgomery, Alabama, provided assistance in selecting and mapping the site. Architect Edward C. Miller and engineer G. L. Washington designed many of the structures. Archie A. Alexander, an engineer and contractor, oversaw construction of the flight school facilities. Tuskegee Institute laborers and skilled workers helped finish the field so that flight training could start on time.

The Army Air Corps assigned officers to oversee the training at Tuskegee Institute/Moton Field. They furnished cadets with textbooks, flying clothes, parachutes, and mechanic suits. Tuskegee Institute, the civilian contractor, provided facilities for the aircraft and personnel, including quarters and a mess for the cadets, hangars and maintenance shops, and offices for Air Corps personnel, flight instructors, ground school instructors, and mechanics. Tuskegee Institute was one of the very few American institutions to own, develop, and control facilities for military flight instruction.

After pilot cadets passed primary flight training at Moton Field, they transferred to Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) to complete their training with the Army Air Corps. TAAF was a full-scale military base (albeit segregated) built by the U.S. military. The facility at Moton Field included two aircraft hangars, a control tower, locker building, clubhouse, wooden offices and storage buildings, brick storage buildings, and a vehicle maintenance area. The base at Tuskegee Army Air Field was closed in 1946. In 1972, a large portion of the air field at Moton Field was deeded to the city of Tuskegee for use as a municipal airport which is still in use today.

Support Personnel

More than 10,000 African-American men and women in military and civilian groups supported the Tuskegee Airmen. They served as flight instructors, officers, bombardiers, navigators, radio technicians, mechanics, air traffic controllers, parachute riggers, and electrical and communications specialists.

Support personnel also included laboratory assistants, cooks, musicians, and supply, fire-fighting, and transportation personnel. Their participation helped paved the way for desegregation of the military that began with President Harry S. Truman's Executive Order 9981 in 1948. The civilian world gradually began to integrate and African Americans entered commercial aviation and the space program.

Benjamin O. Davis

In 1936, Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. was the first African American to graduate from West Point Military Academy in 47 years. First assigned to Fort Benning, Georgia, Davis served as an aide to his father, Brigadier General Davis before transferring to the military science staff at Tuskegee Institute, Alabama.

As one of the first five graduates to get wings at Tuskegee Army Air Field in March 1942, Davis was assigned to the newly activated 99th Fighter Squadron. By August of that year, he became squadron commander. The 99th left for North Africa early in 1943. The group flew many combat missions under Davis' command. Davis returned to the U.S. in September 1943 to assume command of the 332nd Fighter Group. Maj. George S. "Spanky" Roberts remained in Europe and became the commanding officer of the 99th Fighter Squadron.

The fighter group was transferred to Italy in February 1944 where they maintained an outstanding combat record. The 332nd flew bomber escorts. In March 1945, Davis led the 332nd on a 1,600-mile round-trip escort mission to Berlin. During that mission, the Tuskegee Airmen never lost a bomber, despite an onslaught of the latest and fastest enemy German planes. The 332nd won a Distinguished Unit Citation for the mission.

Tags:

#tuskegee#airman,#starzpsychics.com,#starz#advisors

Tuskegee Airmen.

Image: US Army Air Force Training war bond poster featuring a Tuskegee Airman pilot - Tiskegee Airman National Historic Site

In this article from www.nps.gov we learn of the founding and distinctive service of America's unsung black servicemen.

Training for War

Tuskegee, Alabama, became the focal point for the training of African-American military pilots during World War II. Tuskegee Institute received a contract from the military and provided primary flight training while the army built a separate, segregated base, Tuskegee Army Air Field (also referred to as the Advanced Flying School) for advanced training. Support personnel were trained at Chanute Field in Illinois.

The first class, which included student officer Capt. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., began training on July 19, 1941. Rigorous training in subjects such as meteorology, navigation, and instruments was provided in ground school. Successful cadets then transferred to the segregated Tuskegee Army Air Field to complete Army Air Corps pilot training. The Air Corps oversaw training at Tuskegee Institute, providing aircraft, textbooks, flying clothes, parachutes, and mechanic suits while Tuskegee Institute provided full facilities for the aircraft and personnel. Lt. Col. Noel F. Parrish, base commander from 1942-46, worked to lessen the impact of segregation on the cadets.

Image of Eleanor Roosevelt with Charles "Chief" Anderson Many cadets got their primary flight instruction at Moton Field, Tuskegee, from Charles A. "Chief" Anderson. The first class of five African-American aviation cadets earned their silver wings to become the nation's first black military pilots in March 1942. Between 1941 and 1945, Tuskegee trained over 1,000 black aviators for the war effort.

Airmen in Combat

The 99th Fighter Squadron was sent to North Africa in April 1943 for combat duty. They were joined by the 100th, 301st, and 302nd African-American fighter squadrons. Together these squadrons formed the 332nd fighter group. The transition from training to actual combat wasn't always smooth given the racial tensions of the time. However, the Airmen overcame the obstacles posed by segregation. Under the able command of Col. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., the well-trained and highly motivated 332nd flew successful missions over Sicily, the Mediterranean, and North Africa.

Bomber crews named the Tuskegee Airmen "Red-Tail Angels" after the red tail markings on their aircraft. Also known as "Black" or "Lonely Eagles," the German Luftwaffe called them "Black Bird Men." The Tuskegee Airmen flew in the Mediterranean theater of operations. The Airmen completed 15,000 sorties in approximately 1,500 missions, destroyed over 260 enemy aircraft, sank one enemy destroyer, and demolished numerous enemy installations. Several aviators died in combat. The Tuskegee Airmen were awarded numerous high honors, including Distinguished Flying Crosses, Legions of Merit, Silver Stars, Purple Hearts, the Croix de Guerre, and the Red Star of Yugoslavia. A Distinguished Unit Citation was awarded to the 332nd Fighter Group for "outstanding performance and extraordinary heroism" in 1945.

The Tuskegee Airmen of the 477th Bombardment Group never saw action in WWII. However, they staged a peaceful, non-violent protest for equal rights at Freeman Field, Indiana, in April 1945.

Their achievements proved conclusively that the Tuskegee Airmen were highly disciplined and capable fighters. They earned the respect of fellow bomber crews and of military leaders. Having fought America's enemies abroad, the Tuskegee Airmen returned to America to join the struggle to win equality at home.

Moton Field

Moton Field was the only primary flight facility for African-American pilot candidates in the U.S. Army Air Corps (Army Air Forces) during World War II. It was named for Robert Russa Moton, second president of Tuskegee Institute. Moton Field was built between 1940-1942 with funding from the Julius Rosenwald Fund to provide primary flight training under a contract with the U.S. military. Staff from Maxwell Field, Montgomery, Alabama, provided assistance in selecting and mapping the site. Architect Edward C. Miller and engineer G. L. Washington designed many of the structures. Archie A. Alexander, an engineer and contractor, oversaw construction of the flight school facilities. Tuskegee Institute laborers and skilled workers helped finish the field so that flight training could start on time.

The Army Air Corps assigned officers to oversee the training at Tuskegee Institute/Moton Field. They furnished cadets with textbooks, flying clothes, parachutes, and mechanic suits. Tuskegee Institute, the civilian contractor, provided facilities for the aircraft and personnel, including quarters and a mess for the cadets, hangars and maintenance shops, and offices for Air Corps personnel, flight instructors, ground school instructors, and mechanics. Tuskegee Institute was one of the very few American institutions to own, develop, and control facilities for military flight instruction.

After pilot cadets passed primary flight training at Moton Field, they transferred to Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) to complete their training with the Army Air Corps. TAAF was a full-scale military base (albeit segregated) built by the U.S. military. The facility at Moton Field included two aircraft hangars, a control tower, locker building, clubhouse, wooden offices and storage buildings, brick storage buildings, and a vehicle maintenance area. The base at Tuskegee Army Air Field was closed in 1946. In 1972, a large portion of the air field at Moton Field was deeded to the city of Tuskegee for use as a municipal airport which is still in use today.

Support Personnel

More than 10,000 African-American men and women in military and civilian groups supported the Tuskegee Airmen. They served as flight instructors, officers, bombardiers, navigators, radio technicians, mechanics, air traffic controllers, parachute riggers, and electrical and communications specialists.

Support personnel also included laboratory assistants, cooks, musicians, and supply, fire-fighting, and transportation personnel. Their participation helped paved the way for desegregation of the military that began with President Harry S. Truman's Executive Order 9981 in 1948. The civilian world gradually began to integrate and African Americans entered commercial aviation and the space program.

Benjamin O. Davis

In 1936, Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. was the first African American to graduate from West Point Military Academy in 47 years. First assigned to Fort Benning, Georgia, Davis served as an aide to his father, Brigadier General Davis before transferring to the military science staff at Tuskegee Institute, Alabama.

As one of the first five graduates to get wings at Tuskegee Army Air Field in March 1942, Davis was assigned to the newly activated 99th Fighter Squadron. By August of that year, he became squadron commander. The 99th left for North Africa early in 1943. The group flew many combat missions under Davis' command. Davis returned to the U.S. in September 1943 to assume command of the 332nd Fighter Group. Maj. George S. "Spanky" Roberts remained in Europe and became the commanding officer of the 99th Fighter Squadron.

The fighter group was transferred to Italy in February 1944 where they maintained an outstanding combat record. The 332nd flew bomber escorts. In March 1945, Davis led the 332nd on a 1,600-mile round-trip escort mission to Berlin. During that mission, the Tuskegee Airmen never lost a bomber, despite an onslaught of the latest and fastest enemy German planes. The 332nd won a Distinguished Unit Citation for the mission.

Share this article with friends!

Tags:

#tuskegee#airman,#starzpsychics.com,#starz#advisors